Training Intensity Management: Consolidated or Distributed?

Archive post from 10/19/20

Consolidated or distributed intensity is the question of best practices with scheduling strength training and rowing training for continued improvement, energy management, and reduced risk of injury. There are two main different methods with two different theories for efficacy, and no specific research giving us a clear answer. Consolidated intensity describes combining intensities (ie. high/high or low/low), while distributed intensity separates intensities (ie. high/low or low/high).

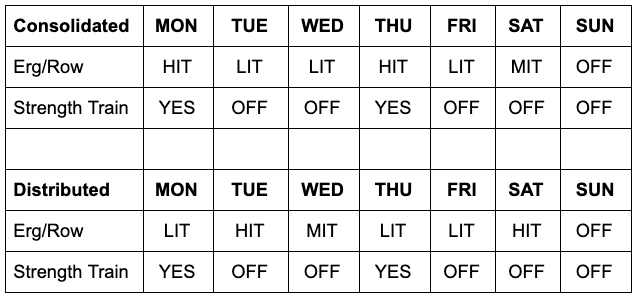

Below is an example of each strategy, using the following general “three-zone” rowing terms: low-intensity (LIT), mid-intensity (MIT), high-intensity (HIT).

Athletes in both systems perform three sessions of LIT, one session of MIT, and two sessions of HIT, with two weekly strength training sessions. The difference is how we schedule training around high-intensity sessions. Those on consolidated schedules will have both of their higher intensity efforts on the same day, so they can dedicate the next day to recovery and low-intensity training. Those on distributed schedules will have no more than one higher intensity effort per day so that recovery is balanced across a whole week of training.

I have found no research demonstrating superiority of one training approach over the other for rowers or similar endurance athletes, let alone research considering different athlete populations and goals within rowing.

In my personal experience, masters rowers tend to prefer the distributed system. Junior and collegiate rowers seem to have too many scheduling concerns to be able to plan training at this level. Those who can, as well as post-collegiate rowers, seem to do either based on which fits their training schedule and preferences. It is challenging to implement this level of training planning given how many variables affect rowers and rowing training. Gym availability, desires of the rowing coach, last-minute changes, and on-water practice conditions can all interfere with the best-laid on-paper plans.

I’ll make some inferences for the following general pros, cons, and considerations for the two approaches.

For an athlete doing a high weekly training volume, I’m more likely to recommend a consolidated approach. Provided enough time (at least 4-6 hours), good nutrition (quantity and quality), hydration, and some moving around to stay loose, the fatigue from the first higher intensity session shouldn’t affect the second session much on the two-a-day days. As long as the muscle soreness from the high-intensity day is not extreme, it is unlikely to affect the lower intensity training of the following day. Athletes doing high volumes of low-intensity training might prefer a consolidated schedule for this reason. For example, the consolidated approach might be particularly beneficial for those following a more polarized training program (~80% low, 5% middle, 15% high). Go hard on your high-intensity days with low volume and strength training, then go really long and easy on your low-intensity days with erging, rowing, or cross-training for high volume.

For a masters athlete or someone doing a more balanced training load, I’m more likely to recommend a distributed system to get the most out of each individual session. The overall weekly intensity or volume might be lower so that athletes can manage a more consistent level of fatigue from more frequent high intensity training. For example, a pyramidal training intensity program (~75% low, 15% middle, 10% high) might be more appropriate here with the more balanced daily training load.

The lack of a clear answer just means that either approach can work given individual preferences and scheduling considerations. Which approach is better for YOU?