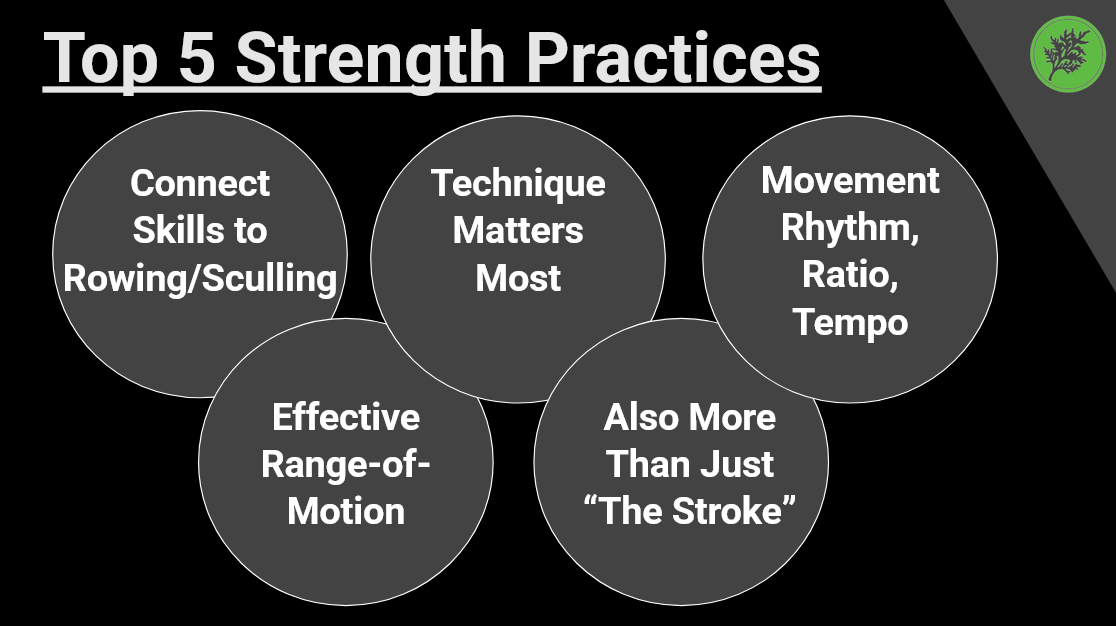

5 Focus Points for Rowing Strength Training

Notes from my presentation to the Green Racing Project Under-23 team

I presented this for the start of the summer U23 rowing program at the Craftsbury Green Racing Project (GRP) last month. I had about 20 minutes to onboard the 15 athletes to the key features of strength training for rowing, GRP Dietitian Megan Chacosky did the same for nutrition, we took some questions, and then we went into the gym for a hip hinge workshop (essentially a live version of this video).

Of course, there are more things! Feel free to add to the discussion via comment below or email reply. The point of this was to pick a salient five to set up the initial instruction session and eight-week summer experience. I hope the five I chose will be useful reminders for long-time readers or a helpful first exposure to newer readers.

#1: Connect the Skills

Strength training is a skill. Rowing (and erging and sculling) is a skill. In the best-case scenario, the skills from one support the skills in the other. If we want that transfer, we have to train for it.

Most of the U23 rowers have spent the prior academic year in big team boats. Some are getting into a single, double, or pair for literally their first time, while others have prior experience and are reacquainting with the subtleties of small boats. It’s a great time to make new technical connections on the water, erg, and in the gym.

We discussed the pitfalls in the advice to “just get stronger,” in terms of quantity of weight or reps with major strength training movements. Improving general force capacity is helpful for many things. When you’re just starting strength training (at any age), it’s all gains at first as you learn new movements, improve coordination, and increase muscle fiber size. After this initial phase of early returns, we need a more targeted stimulus to continue improving transfer to sport-specific performance. The qualities of a movement and how the athlete applies force—the skill—becomes more important than the quantity of force alone. This can be a hard transition for many athletes, especially in a grind-loving sport like rowing.

I asked the group for any of their technical focus points and we discussed how they could move in the gym to support that development. There are constant opportunities to support goal technique in every strength training, erging, cross-training, and rowing session. If we don’t want “junk meters” on the erg or water, then let’s not do “junk reps” in the gym either.

#2: Technique Matters Most

Good movement quality puts the athlete in effective positions to generate, transmit, absorb, and redirect force. This reduces risk of injury and improves transfer to sport performance. We continued the discussion from point #1 with three key “sport-generic” technique features that show up in most strength training exercises:

Full foot contact: I’m always cueing balanced heel/forefoot pressure with quad-dominant rowers (and most other athletes). Watch out for heels lifting off the ground on lower body exercises in particular, especially squats. Full foot pressure improves support, reduces knee stress, and increases glute contribution.

Rib-hip stack: In our seated rockback core exercise tutorial video, friend and fellow rowing strength coach Blake Gourley uses the nice cue of, “like vice-gripping a stack of coins,” to describe keeping the ribs down and braced in alignment with the pelvis. This is also the key to torso support and a neutral spine position in any other exercise: squat, hinge, push, pull, etc.

Shoulders back-and-down: Connect the shoulder blades to the torso for smooth and efficient power production. In the classroom, we went through elevation-vs-depression (shrug up/pack down), protraction-vs-retraction (reach-and-round/pinch back together), and combinations of these movements (like in this video). Start with coordination, address it with some specific exercises, and integrate it into all compound exercises.

#3: Movement Rhythm, Tempo, Ratio

Connect with the rhythm of rowing and control your “recovery” (lowering phase) and accelerate your “drive” (lifting phase). Avoid “reverse ratio” lifting of dropping to the bottom position with little control of the lowering phase, rebounding at the bottom position with the stretch reflex, and then grinding up the lifting phase at a slower speed than the lowering phase. We don’t want to row like this, so let’s not lift like that either. I’ve been going on about this for years, so I’ll just link the video (sound on for voiceover) below.

#4: Effective Range-of-Motion (ROM)

Just like length in the rowing stroke, more ROM with strength training exercises isn’t always better. Think in effective length and effective ROM as the positions that we can actually control and from which we can produce power. This is another productive area of transferable skills between rowing and lifting (for example, this 2016 Rowing Related article).

For more direct transfer to rowing, focus on the positions we want to strengthen for rowing performance. ROM can be too long to transfer. Deeper layback angles in the seated rockback might strengthen the abs, but not the specific point of reversal that we want when rowing. Squatting to a very deep bottom position might benefit the quadriceps, but risks losing hip angle to maximize knee angle or posteriorly tilting the pelvis in a way that we don’t want when rowing. ROM is more often too short to transfer. Three common “ROM loss” faults are high squats, short Romanian deadlifts, and deadlifts with bouncing the weights off the floor between reps.

We can use larger ROM when our goal is more on the muscular development and mobility side versus the specific rowing transfer side. For general muscular development, more ROM is usually better than less. Upper body push and pull exercises should generally be done with as much ROM as the lifter can safely and effectively control rather than in the “stroke ROM,” and usually not in even shorter ROM (eg. half pushups, bodyweight rows not all the way chest-to-bar, chin-ups that aren’t even forehead-ups, etc.). Split squats (rear foot or front foot elevated) to “as much ROM as personally possible” can be great for improving lower body mobility.

#5: Strength Training Is More Than Just the Stroke

With all that said in #1-4, strength training is also about doing things that rowing training doesn’t do. Rowing is excellent for a lot of great things, including aerobic and anaerobic fitness, coordination, community, outdoor recreation, and more. There are still several elements of physical training that we can’t get from only rowing and erging. Strength training can fill these gaps for long-term performance, health, and outside-of-rowing benefits.

Eccentric stress: The rowing stroke is almost entirely concentric, as muscles shorten to produce force without a phase of lengthening under load to absorb or resist force. The missing phase of lengthening under load is a significant stimulus for muscular development, so do strength training and control the lowering phases.

Bone mineral density (BMD): Rowing might increase BMD at the trunk where forces are highest, but only maybe, and it essentially doesn’t in the rest of the body (eg: one study comparing elite rowers to controls). The heavier and direct loading of strength training does increase BMD. This is important regardless of age and competitive level or goals. Bone mineral density peaks at around age 25, so focusing on rowing and erging to the exclusion of loaded movements misses a key phase of healthy development for life.

Lateral and rotational hip movements: Beneficial for low back and hip health (see playlist here).

Upper body push and press movements: Develop the chest, shoulders, and triceps. This can be as simple as an appropriately challenging pushup variation.

Full ROM hip hinge: The seated position of rowing means we’re always in partial hip ROM. Stretch out the hip flexors and strengthen the glutes with full ROM hip extension exercises.

Full ROM shoulder retraction and external rotation: The handle approaching the body reduces shoulder retraction ROM. Shoulder external rotation is absent in the rowing stroke and rare in daily life as well. Do the Y-W-T raise, band pullapart, and band/cable facepull, plus the slightly more nuanced kneeling shoulder raise.

Explosive power movements: The rowing stroke is still pretty slow in force production. I underrated plyometric exercises early in my coaching, but came around to them by early 2020. If we can produce power “way up here” via a plyometric exercise, then the speed of even a power-10 stroke is “way down here” in our overall power capacity. There are also athletic coordination benefits and bone mineral density gains from landing. Throwing plyos are great too, if the impact forces from landing are too much for injured or achy joints.

For more, read a few longer articles on RowingStronger.com:

Such a great article - thank you for posting.

The kneeling shoulder raise looks interesting, I like that you have to support your upper body while doing it